Recently, I visited some of my favorite teachers from high school for the first time since graduating, and I was fully prepared for a small-talk-heavy conversation. I was surprised to have had a dynamic, in-depth conversation about AI ethics with my Spanish teacher, who mentioned her coworkers dubbing ChatGPT as “Chatty,” with an implied distaste of how “she” has transformed education in the last few years.

Señora was ecstatic to discuss the limitations and capabilities of AI technology with me. She explained how her AP Spanish class uses ChatGPT on occasion for conversational practice, but she and her students critically engage with its nonsensical outputs and hallucinations. We discussed our disappointment over Duolingo’s CEO announcing their AI-first agenda (and then somewhat walking back their claim amidst the controversy) and how this replacement of humanity in the learning experience negatively impacts accessible language learning and consequently culture learning, given the inextricable relationship between language and culture.

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, I took a course on linguistic anthropology that, dare I say, lowkey changed my life. In our first paper assignment, our professor wanted us to argue about the linguistic incompetence of ChatGPT and other LLMs based on the readings and lectures we had consumed over the past few months. Honestly, I was quite excited the opportunity to synthesize my technical and mathematical understanding of AI with the new sociocultural understanding I recently attained. I remember our professor explicitly banning AI use in this assignment, pushing us to truly immerse ourselves in the course content and think for ourselves about linguistic competence and the subtle ways ChatGPT pushed Noam Chomsky (the father of modern linguistics to most) to contradict his own beliefs. Our professor explained that some day we would all be challenged to take a stance on AI models and LLMs, regardless of our future trajectories. I am ashamed to have doubted his foresight, less than a year after GPT-3.5 was made public, and I am extremely grateful for how this course and this assignment shaped how I engage in conversations regarding AI and humanity. More recently, I feel grateful for the long hours at Central Library, dissecting and distilling challenging assigned readings, that prepared me for such a lively discussion with my high school Spanish teacher.

Though ChatGPT as well as other LLMs have evolved since taking that course, Noam Chomsky’s critiques of ChatGPT’s lack of a personal perspective and moral indifference still ring true. Even now, with Claude, Gemini, Copilot, Grok, and others, LLMs continue to respond to moral dilemmas with a heavily “centrist” perspective, failing to deliver any meaningful points given their lack of nuance and social experience that is fundamental to the human language experience. Rather than heeding Chomsky’s warnings regarding the ChatGPT’s linguistic incompetence, AI has grown and immersed itself into every aspect of everyday life. Many folks have, instead, equated LLMs’ abilities to wield language to humans’, as seen in the rise of people using ChatGPT as low-cost or free therapists, significant others, and the writers of academic essays. It is the norm to see companies replacing irreplaceable human resources (e.g., language and culture experts at Duolingo, entertainment companies wanting AI to replace writers, etc.) with incompetent AI resources.

“Artificial intelligence, more than likely, will continue to grow and immerse itself into every aspect of everyday life. Although we, as a society, cannot necessarily control the ways that it will impact our daily lives, we can at the very least be cautious and critical of how it is used, acknowledge its computational power for what it is, and avoid equating its abilities with our minds that required millions of years of evolution to refine… Artificial intelligence’s true danger lies within the potential for humans to succumb to the narrative that AI—with its incapabilities of debating nuances of moral arguments and constantly defaulting to its creators—is truly intelligent.”

- me in 2023

In my AI ethics course this past semester, our professor explicitly asked students to keep their AI usage to a minimum and asked for transparency regarding their usage. She allowed us to use AI as a resource for learning and understanding course content, but not to complete response assignments as a whole. Despite this, the conversations I overheard in class were of students finding elaborate ways to put in zero effort and critical thinking (these assignments were extremely low-stakes reflections that take 10 minutes tops if you complete the reading, mind you). The entire course was labeled by most students as low-effort despite the readings and lectures discussing severe instances of AI being deployed for malicious purposes to perpetuate systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and more. If you’ve ever seen Don’t Look Up (2021), I felt like Jennifer Lawrence’s character. At this point, I am not sure what kind of AI “accident” needs to happen before ethics becomes a personal issue for students in a data science Master’s program.

I had the most fascinating (and I mean this ironically, of course) debates with some classmates in this course. Our professor once asked us to discuss whether AI should be restricted for children aged 17 and under. In light of the character.ai incident, I suggested that as long as AI literacy and guardrails could be implemented with the help of child development experts and in conversation with both parents and kids, children should have some access to AI capabilities as a method to study or support their learning. My approach to my argument was reflective of my personal experience growing up on the Internet; because of my experiences and digital literacy taught in schools and by my parents, I was a cautious Internet user who felt relatively safe exploring the Internet for myself. I certainly would not say that I am anti-AI usage (hell, my academic life revolves around data science), but there are clear and feasible guidelines that must be integrated into these technologies to safeguard children and other vulnerable populations.

One of my peers, who, on paper, is very talented in his area of research but has no experience with living in poverty whatsoever, argued that because OpenAI released ChatGPT with the goal of making education more accessible, AI models should have little to no restrictions or regulations for all. He followed up by explaining how children in Third World countries may not have access to proper educational institutions but should at least have unrestricted access to local LLMs on their smartphones so they can learn and improve their socioeconomic situations on their own. I could not believe my ears… Also, if these kids are living in poverty, what makes you think their priorities are education (via AI, no less)? What happened to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs???

I digress. Back to the point of AI literacy. I would not be the first on Substack to rant about the trend of decreasing literacy of all forms in the United States, and I am not at all surprised by the lack of support for AI literacy programs on a government and corporate level1. Companies with the most capability to work toward safe versions of LLMs, especially in regards to protecting children, do not do so because they do not see an immediate and concrete return on investment. AI-infused education has the potential to break down existing systemic barriers to quality education and assist teachers in tasks, but it is nowhere near where it needs to be. A broken education system, in which students are struggling to read at an appropriate grade level, cannot be improved by merely throwing AI into the mix.

Numerous classic dystopian novels warn readers that a lack of literacy of all forms creates a more complacent, compliant, and vulnerable population (thank you, Ray Bradbury). A population wholly reliant on AI for critical thinking skills, moral takes, and tasks that genuinely help grow your brain is at high risk for exploitation. Until we collectively acknowledge the uniqueness of human language and the years of evolution that led to our communication abilities today, we allow the false equivalency of AI to human intelligence, putting human flourishing at risk of extinction.

The Ship of Theseus is pretty applicable in this scenario. If you didn’t watch WandaVision (2021) (rip), this classic philosophical thought experiment essentially asks whether a ship that has its pieces replaced over time remains the same ship throughout this process. If we rely on AI for mundane tasks but remain resistant to using it for larger tasks that require a great deal of thought, maybe we can argue that our brains are freed up from a cognitive load, that we are freeing up time for more important things. When we become reliant on AI for the Hard Stuff (synthesizing information, making important decisions, replying to texts, or forming a personal understanding of something) or the Creative Stuff (writing a song, drawing a portrait of your mom, or even writing fan fiction), how much of your brain or your thoughts remains yours? How much is unchecked centrist bullshit, potential hallucinations, and AI slop?2

Like I discussed in a previous post, I have become rather wary (as best I can) of the data I provide to various websites and third-party applications. I think it’s important in this time of technofeudalism (more on this soon) to be more careful about the data we “freely” offer in order to access certain websites online and considerate regarding how it can be weaponized against us for monetary gain and/or surveillance’s sake. Don’t get it twisted—I’m not saying to take on a Parks and Recreation’s Ron Swanson off-the-grid doomsday survivalist lifestyle, but work towards mindfully consuming media and cautiously engaging with products as a consumer.

To extend the Ship of Theseus framework to consumerism, consider recommendation systems. As I freely offer my preferences, user activity, and behavioral data to data brokers, proprietary algorithms deduce my interests, hobbies, and inclinations. Using this information, they feed me what they hope I will take interest in, and the cycle starts again. The more data, the more refined the recommendation system is to me. The more data, the more money companies can make off selling it to other companies. Eventually, after numerous iterations of retraining and fine-tuning the AI models, the recommendation system is spot-on. Are the interests that the model deduced my true interests? How many iterations of retraining must I peel back to reach my original interest, hobbies, and inclinations? Do I have to reach the core, before my user activity data was collected and fed into these algorithms?

“The same algorithm that we help train in real time to know us inside out, both modifies our preferences and administers the selection and delivery of commodities that will satisfy these preferences.”

From Technofeudalism - What Killed Capitalism by Yanis Varoufakis

I recently read Yanis Varoufakis’s book on technofeudalism3, which uses numerous metaphors to help readers understand the dire situation of our current economic system. Capitalism relied on the ability to commodify things, slapping an exchange value on practically everything. The rise of the internet and the age of information brings about a new economic system, where we users become the serfs. Varoufakis uses the example of Amazon’s Alexa and how users “train” it to eventually train them into certain behaviors. But considering the opacity regarding how users’ data and voice recordings are used, we users are the ones being exploited while the feudal lords (the oligarchs of America) gain cloud capital and thus political power.

This point, in combination with Varoufakis’s comparison of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to “a cloud-based sweatshop where workers are paid piece rates to work virtually,” reminds me of something we serf users of the Internet cannot avoid: CAPTCHAs (which stands for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart). Yeah, insane acronym. On the surface, these verify human users, but what they do not reveal upfront is that your answers help train their AI systems. Something that requires a great deal of human input in the world of AI is labeled datasets for training—robust datasets that have a set of examples with an associated ground truth. By showing we are not robots, we help improve robot intelligence… except most people aren’t aware they’re doing it.

On the topic of transparency, Atlas of AI by Kate Crawford illustrates how technological supply chains, in particular, are kept opaque from everyday folks. This strategic business decision maximizes the amount of exploitation that can take place at all stages of the labor flow, from mining and extracting materials to manufacturing and assembly, and every transportation stage in between. The less customers know about the blood, sweat, and tears required to mine raw materials, transform them into products, and transport products to your door, the less guilty they feel for engaging in consumerism, purchasing items off Amazon will-nilly, knowing they can always easily return the item.

Just like the mines that served San Francisco in the nineteenth century, extraction for the technology sector is done by keeping the real costs out of sight. Ignorance of the supply chain is baked into capitalism, from the way businesses protect themselves through third-party contractors and suppliers to the way goods are marketed and advertised to consumers. More than plausible deniability, it has become a well-practiced form of bad faith: the left hand cannot know what the right hand is doing, which requires increasingly lavish, baroque, and complex forms of distancing.

From Atlas of AI by Kate Crawford

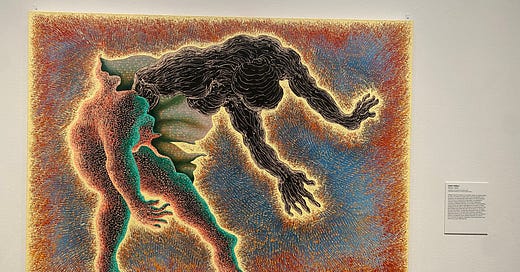

AI and technofeudalism flourish in a world of supply chain ignorance, where the population takes a centrist approach to life, avoidant of critical thinking that may be deemed “radical.” It thrives in a collective avoidance of mental growth, an offloading of mentally and emotionally challenging tasks to artificially “intelligent” machines. At this turning point of humankind, we have a duty to protect humanity and human experiences of language, culture, art. Read a book that challenges your brain and forces you to learn new vocabulary. Engross yourself in some human-produced art at your local art museum. Stare at it for a super long time and appreciate how much time and effort and soul was put into the piece. Try eating a new restaurant with a menu full of foods you have never seen before and names you can’t pronounce. Ask your friends how they use AI and discuss why they might use it for certain tasks (bonus points if you have a fruitful conversation about what ethical AI use could look like).

I recently listened to this podcast episode with Rebecca Winthrop, a global education expert, for another perspective on AI in the classroom.

This timely video essay by tiffanyferg came out while I was outlining this post. She focuses primarily on the critical thinking aspect but brings up a lot of important points.

The only reason I would not recommend this book to anyone and everyone is due to his style of writing and somewhat convoluted way of getting at his points. Honestly, if he wrote an abridged version in a research paper tone, it would actually be easier to read. Good content, though.