Like the rest of the world, I’ve been watching White Lotus Season 3 (in addition to its companion podcast) recently, and episode 3 jolted me back to remembering how deeply entrenched I was in evangelical Christianity and how this has led to issues throughout my life. No spoilers here, but the underlying themes of this episode and the drama between the 3 girl friends reminded me of something that happened last year that I have still yet to fully process.

I understand the story of the original sin (or Genesis 3, if we’re being specific) to be a commentary on the balance of power, of maintaining the balance between an all-knowing, all-powerful God and the weak, mortal man. I also understand the story to be a warning against Satan’s temptations and disobeying the higher power. These takeaways are all no-brainers to me. I lived and breathed this story and its societal reverberations for more than a decade of my life.

Something that I had immense difficulty wrapping my mind around as a child, though, was this story’s implied message about seeking knowledge. As a young, knowledge-seeking child, I could not fathom why desiring knowledge and understanding of good and evil was so wrong. The NIV version of Genesis 3 even describes one of Eve’s motivations to be a “desir[e] for gaining wisdom.” Why was the original sin, in part, rooted in a desire for knowing and understanding the world?

I let that question hover in the back of my mind for the better part of my childhood, but I never let it take up much space. Church leaders often warned us of the dangers of higher education and how, statistically, many who grow up in the church move away from religion by graduation. They warned us about how the types of professors and classmates we would encounter in college would be a direct threat to our faith. Growing up, my dad always told me that the root of most social issues is a lack of education or a lack of access to it. In more recent years, my dad, who (thank god) has always been a skeptic, brought up the idea of knowledge and education as a direct threat to the institution of evangelical Christianity. That’s when things started to click for me.

As a kid, I was thrown off by the mixed messaging I received from church leaders. Some encouraged doubts as a normal part of the religious experience, while others jokingly implied that “Doubting Thomas[es]” were less Christian than them. Taking after my dad, I tried to push back against certain aspects of Christianity that didn’t make sense in a logical and social sense for me. I questioned ideas and norms, but I don’t think I ever overstepped (thinking back on it now, I wish I had pushed further, but I’m not sure I was mentally and emotionally prepared for that). Whenever discussions over science vs faith showed up in Sunday School, my dad would always remind me that new scientific breakthroughs should enrich faith, not oppose it.

The answer to all of my doubts, my leaders said, was faith—faith in the unknown occupied by God, faith that God will work out the finer details, faith that “knowing things” was God’s job and not ours. This answer satisfied me until I felt the weight of the world and social structures and injustices at age 13 (not saying I didn’t recognize injustices existed before then, but the weight of it all didn’t hit nearly as hard until 13).

I was a pretty anxious child, and I was relatively vocal about my anxieties and fears with people at church. The common response to these feelings, however, was always some iteration of the hollow saying, “Let your faith be bigger than your fear.” In practice, this makes zero sense. There were clear issues at the root of my anxiety that should have been addressed, but instead, I carried on, blanketing my anxiety with “faith.”

All this to say, I began to realize in high school that my faith community was highly supportive of a particular political ideology than another—one that takes away funding from public education, attempts to ban books that question hegemony, thrives on misinformation, and reduces access to knowledge altogether. This, in addition to a standard amount of empathy, is what radicalized me. Taking away high-quality, accessible education from the public is at the heart of fascism, and my heart breaks for the low-income folks in the South who were caught up in empty promises and are ultimately victimized by the current administration.

The night of the 2024 election, I sat at my kitchen counter numbly refreshing the New York Times election map, permeating with red. My shoulders felt heavy the days after the election, and everything I had planned that week felt futile. Seeing hometown friends post in celebration of the election pushed me (mentally) over the edge, so I did something I would not recommend anyone do. I made a long Facebook post.

Today, I have carried this heavy feeling of anguish and betrayal from the people I grew up with.

What is so deeply unsettling to me is how hateful the community I was raised in has proved itself to be. The community that preached loving your neighbor and caring for the less fortunate. The community that taught me to volunteer my time and speak up for what I believe in.

This is also the same community that bullied me and targeted me with microaggressions because I looked nothing like them. The community that exploited my experiences with mental health for the sake of “sharing my testimony”. The community that I realized I would never fit into at age 5.

Despite all of this, I chose hope. I hoped you would choose love over hate. I hoped that you would open your hearts and minds to truly loving and caring for the “less fortunate” you claim to care about. I hoped that behind the veil of Christianity, you truly did want to embody Jesus’s character. But instead, you delight in a rapist, racist, and deeply hateful and evil person who has promised destruction to the least fortunate in this society returning to power. You choose white supremacy and oppression time and time again. You choose hatred over cold, hard research-based facts. You chose selfishness during a worldwide pandemic.

And I still held out hope. I held out hope that you would think back to when we were younger and you told me how much you appreciated me and my faith and my insights on Christianity. I held out hope that you really meant it when you said “I love you.” I held out hope when you said you would be praying for my family. I held out hope that you actually cared about my existence. I held out hope that you would care even a little bit about basic human rights.

Every time, you fail me. You never meant any of it. And to think that I really believed that people cared.

And to you all who posted “No matter what, Jesus is King” or “A sign of maturity is agreeing to disagree,” you’re included in this. You, standing off to the sidelines, trying to maintain a “neutral” point of view. You don’t get to escape this one. You are also responsible for the blood that has and will be shed because of this presidency. By opting out or staying “neutral,” you are exercising your privilege and siding with hate. You, too, are hiding behind the veil of Christianity by deciding the basic human rights of your children and neighbors is not worth voting for “the other side.” Claiming that it’s okay to agree to disagree on the very existence of millions of people is not maturity—it’s pure evil.

(And I don’t care that your “vote didn’t matter” in your state. It’s the principle of it all. You should know that.)

I choose to hope in a better future because of what we learned together as children in Sunday School. But you—you take the same texts I read and somehow use it to justify white supremacy and the oppression of anyone that does not look or think the same way as you. You will never understand the enormous privilege that you have, and on top of that, you have not even *attempted* to empathize with and listen to anyone with less. I have no respect for you. I can only pray that you wake up one day and realize the damage you have done. May that haunt you forever.

Okay, maybe it was a bit harsh, but it was a bad week, and I needed to get it all off my chest. I got some ominous comments from my parents’ old church friends, but I also received a bit of support from high school acquaintances and past teachers and mentors, which was pretty comforting. For the most part, I just left the post up and didn’t bother to check on it.

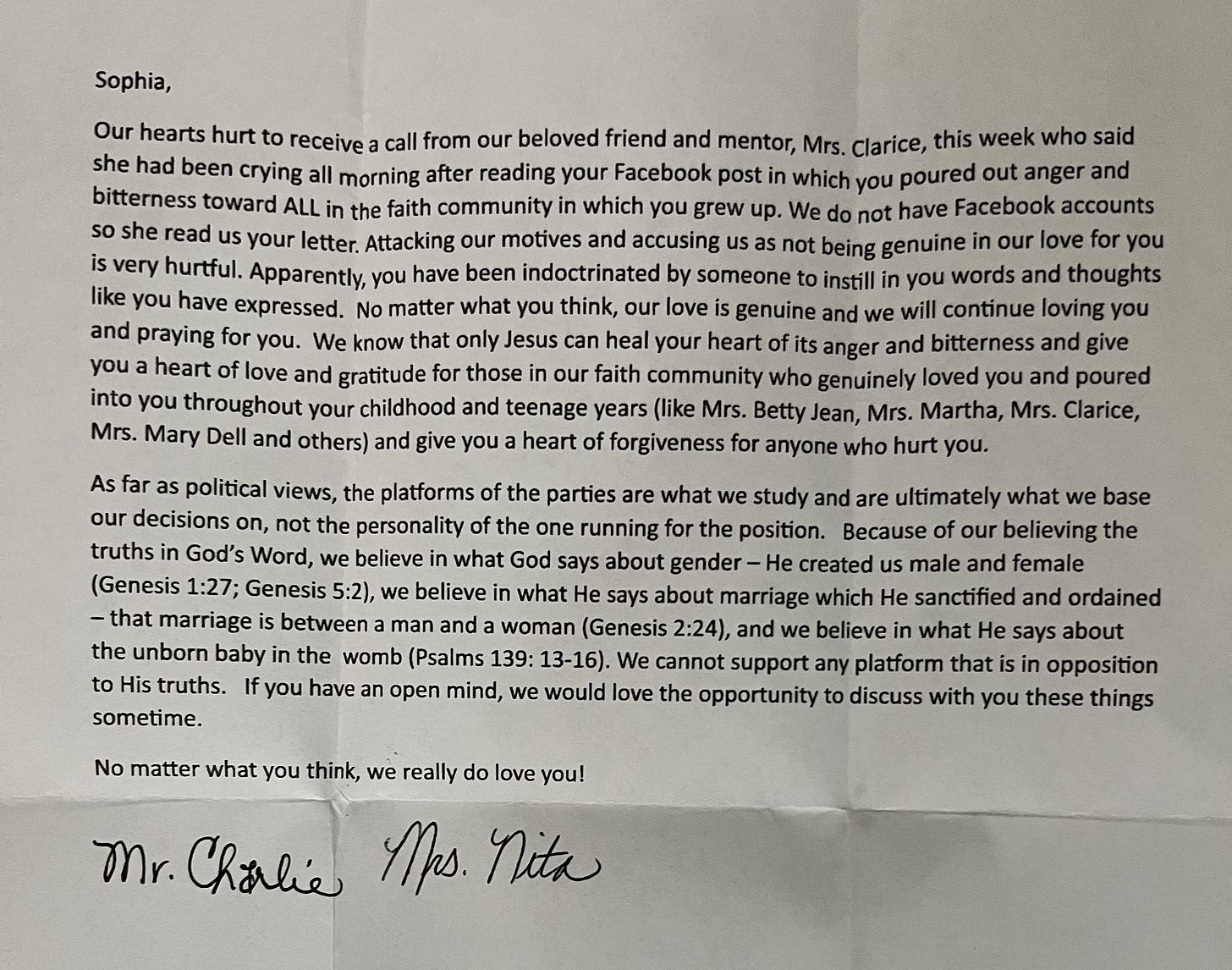

The next week, I got a text from my mom: Mr. Charlie sent you a letter. Since these are only first names (and extremely common names at that), I don’t care enough to put them behind pseudonyms.

Even now, almost 4 months later, I am a little speechless each time I read the letter. Putting the social impact of supporting Tr*mp, the cognitive dissonance, and the emotional manipulation aside (wow), what bothered me most about this letter was the way they implied that I was brainwashed or hurt by some third party or that I couldn’t have reached my political ideology on my own. Practically every college student taking a humanities course (sociology, anthropology, etc.) can see how power structures are intertwined and lead to the mass destruction of people and places. I have seen firsthand how the rhetoric pushed by these particular leaders causes direct harm to their students (my parents, for example). I have seen how they disguise their dislike (and often hatred!) for people daring to challenge their norm using Christianese, niceties, and religious texts. To imply that I had to be “indoctrinated” to come to this conclusion baffles me.

I recently watched Conclave (2024) and LOVED IT in case you were wondering1. The film comments on a myriad of topical themes, and I will be thinking about it for a very long time. This quote struck me in particular:

The greatest sin is certainty. Certainty is the enemy of union. Certainty is the enemy of tolerance… Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand-in-hand with doubt. If there was only certainty and no doubt, there would be no mystery. And therefore no need for faith.

Evangelical Christians moan all day about how they are the ones under attack, that there is a culture war against their traditional values, despite historically holding the majority of power in Western society. All the decisions in evangelical Christianity have been made—they speak in absolutes, certain about what God thinks about x, y, and z (despite switching up on their ideologies for monetary and power-related reasons on a macro level2).

There’s a real fundamental issue to fundamental Christianity, and it’s that while scripture might be God-breathed, so-called fundamental interpretations are not. Do you know just how difficult it is to interpret an ancient text that has undergone multiple iterations and translations and versions with limited context? You cannot shame a more liberal Christian for cherry-picking scripture when you do the exact same (and perpetuate hatred towards millions of people in doing so).

After years of wrestling with the label of Christianity, I let it go, opting for agnostic. I’ve dissected the habitus and cognitive dissonance of evangelical Christianity in as many of my undergraduate courses as possible, and it has been so refreshing to examine it all through an anthropological lens. But I’d be remiss not to mention that I miss Christianity to a degree. I miss the spiritual aspect, spending silent alone time in gratitude for the people placed in my life and the people I had yet to meet and how I was predestined to experience certain things. I miss praying for my faith community and them praying for me (or so they said) and simply feeling deeply known by others.

I often wonder who I would be today if I had been raised in a different religious context. Would I have reached my current worldview somehow? Would my core values be any different? (I would probably be more mentally stable… but whatever)

I am never certain about anything these days. And in some ways, that uncertainty is what fuels my spirit. What I miss so dearly about my faith is the awe I had for the mystery of it all. But sometimes, I feel more connected to God—or whatever higher power—now through faith and hope, as an agnostic, than ever before.

What I realize now is that faith is not a direct conqueror of fear, nor is it the enemy of knowledge. Knowledge and uncertainty can co-exist, allowing faith and knowledge to do the same. When faith is weaponized the way it has, wisdom is at stake.

Genuinely, please watch Conclave if you haven’t already. It’s streaming on Peacock if you subscribe to that for whatever reason.

https://www.npr.org/2022/05/08/1097514184/how-abortion-became-a-mobilizing-issue-among-the-religious-right